Principle of Corporate Climate Responsibility for Climate Damages Established – The Lliuya Decision

By Estelle Dehon KC

Climate litigation has taken another step forward with the decision of the Higher Regional Court of Hamm in the case of Lliuya v RWE: the first decision by a higher court in Europe to affirm that companies can, in principle, be held civilly liable for the harms caused by their contribution to climate change. While the action, based in German property law, ultimately failed because the claimant was unable to prove the specific pleaded real an imminent risk to his property, the in-principle arguments pleaded in defence about the lack of justiciability of climate harms and lack of causation, were roundly rejected.

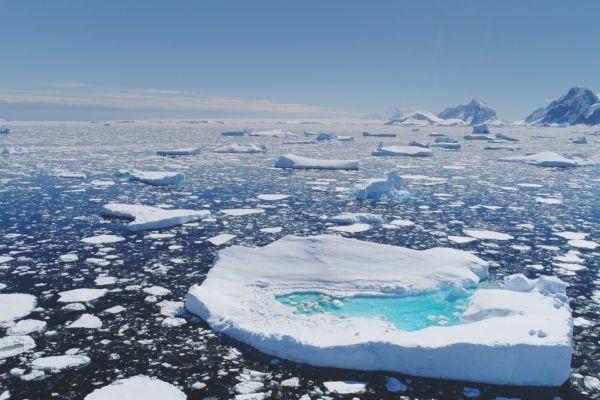

First filed in 2015, the claim was brought by farmer and mountain guide Saúl Luciano Lliuya, whose home, situated in the city of Huaraz below the glacial Lake Palcacocha in the Peruvian Andes, is threatened by flood risk due to climate change-induced glacial melt. RWE Group is Germany’s largest electricity producer and is a “Carbon Major”, having had longstanding involvement in coal mining. It is responsible for between 0.38 and 0.47% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions since from 1965 to 2010. The claimant sought a declaration that the defendant was obliged to bear the costs of suitable protective measures for his property against a glacier flood in proportion to its contribution to global GHG emissions; or alternatively that the defendant take proportionate action to reduce the risk or pay proportionate damages to the Waraq community association and himself.

Four Key Takeaways

The decision affirms the principle that companies can be held accountable for the damage already caused by their past emissions. Four aspects are notable.

Climate attribution science: The claimant’s case relied strongly on climate attribution science, which provides evidence linking human-caused increases in atmospheric GHG concentrations to specific harmful impacts. The Court confirmed that climate science can provide a basis for holding companies liable for their contribution to climate-related risks. It recognised that emissions from a specific company may be linked to real-world climate impacts, such as glacial melt and resulting increased flood risk.

Causation: Of significant interest is the approach that the Court took to causation and the role of the parent company, RWE Group. The Court found that:

- even if there were multiple links in the causal chain, and only an indirect connection between RWE Group’s actions and the climate harm caused by glacial retreat, “the attribution criteria required by case law would be fulfilled”;

- the cumulative, distant and long-term consequential nature of the damages did not exclude the possibility of civil liability; and

- there was a factual basis for causation, as the parent company’s “fundamental entrepreneurial decision”, freely undertaken, “caused emissions of large quantities of CO2 [through] the construction and operation of the greenhouse gas-emitting power plants”; “it derives economic benefit from coal-fired power generation and the inevitable release of hundreds of millions of tons of CO2 into the atmosphere” and it has the “scientific and legal expertise” to assess the risk from that pollution.

Interestingly, these findings echo the approach to legal causation taken by the UK Supreme Court in the public law context in Finch v Surrey County Council [2024] UKSC 20, concerning whether a company applying for permission to extract fossil fuel for production “controls” the indirect combustion emissions from the burning of the oil. Lord Leggatt held at §103:

“The combustion emissions are manifestly not outwith the control of the site operators. They are entirely within their control. If no oil is extracted, no combustion emissions will occur. Conversely, any extraction of oil by the site operators will in due course result in GHG emissions upon its inevitable combustion. It is true that the time and place at which the combustion takes place are not within the control of the site operators. But the effect of the combustion emissions on climate does not depend on when or where the combustion takes place.”

Foreseeability: The claimant argued, based on a study by Charles D Keeling (giving rise to the well-known Keeling Curve), that it was foreseeable from 1958 onwards that increasing CO2 emissions would lead to global warming, with its associated harmful consequences. The defendant argued that such foreseeability could only, at the earliest, be assumed in 1992 with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Court held that from at least 1965 onwards, major emitters could reasonably foresee the harmful consequences of their actions, including contributing to the melting of glaciers.

Justiciability: The defendant argued that there was no legal basis for an individual company to be liable for the alleged consequences of climate change; that he courts would be overburdened if such claims were allowed and that solutions to climate change can only be implemented at state and political level. The Court rejected this, clarifying that civil claims relating to the impacts of climate change fall within the judiciary’s purview and do not infringe on the domain of politics or violate the principle of separation of powers. While the climate crisis requires political solutions, courts are fully competent to adjudicate individual civil claims for injunctive relief or damages. Such legal scrutiny is not only permissible but a constitutional function of civil justice.

Impact of the Decision

It will be interesting to see if the Lliuya decision will have an impact in civil proceedings in the UK. The German system is in some respects quite different from that in the UK – for example, the German Court did not go on to consider whether RWE’s actions amounted to a breach of a possible duty of care, as that was not needed to establish potential liability. The approach to legal causation and to foreseeability does, however, appear to be similar, so may be deployed before courts in the UK. The acceptance of climate attribution science will certainly be influential.

The judgment is available in (slightly ropey) English translation here.