Renters (Reform) Bill: The impact on the social housing sector

Andy Lane considers the impact of 3 proposed reforms to housing law found in the Renters (Reform) Bill

The long-awaited Renters (Reform) Bill (“the Bill”) received its 1st Reading in the House of Commons on 17 May 2023 amidst a flurry of media and government comment on its potential impact on the private rented sector (“PRS”). For example:

“The Renters (Reform) Bill will improve the system for both the 11 million private renters and 2.3 million landlords in England.’ (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’ “Guide to the Renters Reform Bill”).

However, whilst it’s undoubtedly right to say that the potential impact of these reforms will be more radical on the PRS, the social sector in the form of private registered providers of social housing (“PRPs” – housing associations, etc) will also have to review their operations. This is particularly true in 3 areas which I will briefly focus on in this article:

- Security of tenure – ie. the ending of assured shorthold tenancies (“AST”).

- Additional/revised grounds of possession.

- Shared ownership.

Security of tenure

All tenancies in the non-local authority social sector will, assuming the Bill is passed in something approaching its current form and excusing Schedule 1 arrangements, be assured non-shorthold tenancies (“ATs”) and thus provide security of tenure. They will also have to be periodic (no longer than monthly) and cannot be fixed-term[1].

That latter reform is not, I would suggest, unpopular and it may be recalled that a number of years ago now a number of PRPs, such as the London & Quadrant Housing Trust[2], ditching their fixed term models in favour of the periodic arrangement previously seen as the norm.

Demoted orders[3], whereby ATs become ASTs, have never proved to be a common or popular order for PRPs and so their passing will be of little consequence. Rather, the immediate question for PRPs arising from the abolition of ASTs is how it will impact upon starter tenancies, or those tenancy arrangements where the available and anticipated tenancy life is legitimately limited?

In respect of the former, there will be nothing to stop a PRP still utilising “starter tenancies” once the Bill is finally passed, ideally by reference to a separate term(s) in the standard agreement, because what that is saying is that there is a probationary period during or at the end of which the tenant(s) has been either ‘passed’ or ‘failed’.

If they have failed that almost inevitably must be because of a breach of tenancy of some description such that a ground for possession can be satisfied – e.g. ground 11 (persistent delay in paying the rent), ground 12 (breach of tenancy) or ground 14 (anti-social conduct) – and pursued in the form of possession proceedings.

Though such action could be taken in any event of course, a PRP’s policies (which will need to be revised in light of the reforms if and when implemented) and/or tenancy conditions may provide for their more likely and quicker use in cases of “starter tenancy”, and insofar as reasonableness and/or proportionality needs to be demonstrated then the clear and stated purpose of that initial period of tenancy would generally support the PRPs’ case.

As for a PRP’s anticipated need to recover the premises through no fault of the tenant – e.g. the superior landlord wants the return of the accommodation – a variety of options arise, such as:

Mandatory

- Ground 6 (intention to demolish/reconstruct)

- The new Ground 2ZA (superior landlord has given valid notice to terminate)

- The new Ground 5B (accommodation needed for landlord’s employee)

- Ground 5D (used to be Ground 16 – no longer in employment)

Discretionary

- Ground 9 (suitable alternative accommodation will be available for the tenant)

It must follow that the changes to security of tenure and loss of the section 21 route to recovery of possession need not have a negative change on the sector at all. This is especially so when one considers the Tenancy Standard at 2.2.2:

“Registered providers must grant general needs tenants a periodic secure or assured (excluding periodic assured shorthold) tenancy, or a tenancy for a minimum fixed term of five years, or exceptionally, a tenancy for a minimum fixed term of no less than two years, in addition to any probationary tenancy period.”

Grounds of possession

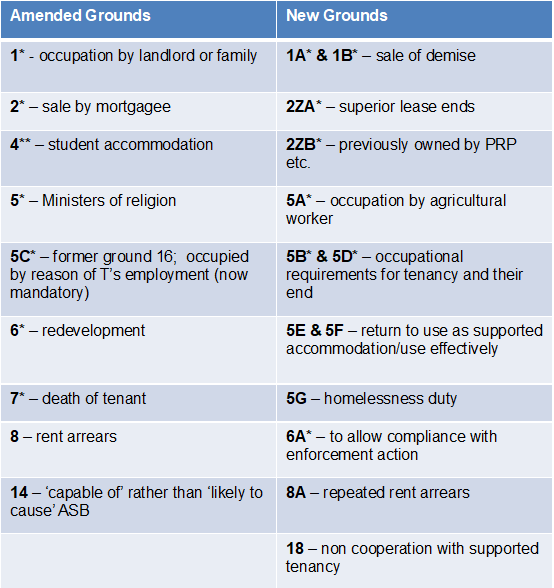

This article has already touched upon some new grounds for possession and at the recent webinar on the Bill which Jack Barber and I presented the following aide-mémoire was used (I have deleted the reference to the repealed holiday accommodation ground 3):

Of most obvious immediate interest to PRPs are 2 of the grounds – the amended ground 14 and the new ground 8A. Ground 14 is the discretionary anti-social conduct ground which presently says:

The tenant or a person residing in or visiting the dwelling-house—

“(a) has been guilty of conduct causing or likely to capable of causing a nuisance or annoyance to a person residing, visiting or otherwise engaging in a lawful activity in the locality,

(aa) has been guilty of conduct causing or likely to capable of causing a nuisance or annoyance to the landlord of the dwelling-house, or a person employed (whether or not by the landlord) in connection with the exercise of the landlord’s housing management functions, and that is directly or indirectly related to or affects those functions, or

(b) has been convicted of—

(i) using the dwelling-house or allowing it to be used for immoral or illegal purposes, or

(ii) an indictable offence committed in, or in the locality of, the dwelling-house.”

The ‘simple’ change is marked above and it may be worthy of note that the ‘anti-social behaviour’ definition in Part 1 of the Antisocial Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 (i.e. anti-social behaviour injunctions) is to an extent mirroring the proposed revision, with emphasis added:

“(a) conduct that has caused, or is likely to cause, harassment, alarm or distress to any person,

(b) conduct capable of causing nuisance or annoyance to a person in relation to that person’s occupation of residential premises, or

(c) conduct capable of causing housing-related nuisance or annoyance to any person.”

I will leave the final words on this issue to the Bill’s Explanatory Notes, at paragraph 617:

“Landlords previously had to demonstrate that behaviour was “likely to cause” a nuisance or annoyance. This is being widened to include “capable of causing” so that a wider range of behaviours can be considered by the court. The ground is discretionary, so judges must consider whether eviction is a reasonable and proportionate response to the behaviour in question.”

Of greater controversy is a new (mandatory) ground for rent arrears – Ground 8A:

“Within a three year period ending with the date of service of the notice under section 8—

(a) if rent is payable monthly, at least two months’ rent was unpaid for at least a day on at least three separate occasions, or

(b) if rent is payable for a period shorter than a month, at least eight weeks’ rent was unpaid for at least a day on at least three separate occasions.

For the purposes of this ground, occasions are “separate” if in between those occasions the amount of the unpaid rent reduced to less than the amount mentioned in sub-paragraph (a) or sub-paragraph (b) (whichever is applicable) for at least one day. When calculating how much rent is unpaid for the purpose of this ground, if the tenant is entitled to receive an amount for housing as part of an award of universal credit under Part 1 of the Welfare Reform Act 2012, any amount that was unpaid only because the tenant had not yet received the payment of that award is to be ignored. For the purposes of this ground, “rent” means rent lawfully due from the tenant.”

Whilst it is fair to say it does factor in universal credit housing costs which remain unpaid, as does ground 8 under the proposed amendments, to some degree this new ground simply adds a mandatory flavour to a tenant who is not good at maintaining their rent account (for whatever reason) – i.e. the persistent delay (discretionary) ground 11. It also potentially causes a dilemma for a tenant who does not want to fall foul of its provisions by “dipping” below the 2 months/8 weeks arrears figure for a 3rd time.

The reality is that it is another ground available to landlords to use in rent arrears cases, but as with the application of the existing (mandatory) ground 8, PRPs will want to be sure their rent policies address when 8A should be used and properly consider the appropriateness and proportionality of its use (particularly from a discrimination perspective) before deciding on reliance.

The Explanatory Notes to the Bill say, at paragraph 60, that the changes to the Schedule 2 Grounds are in order to provide balance between the interests of landlords and tenants. Whether that will be successful remains to be seen.

As for related matters arising from the Bill:

- A landlord will be able to issue a Ground 7A possession claim immediately after service of the notice (28 days at present) – this does not factor in reviews presently carried out by most PRPs, although the issue of proceedings does not have to be immediate.

- There are longer periods of notice – 4 weeks – for rent grounds (14 days at present) – s.8(4AA): and Grounds 5E, 5F, 5G, 8A & 18.

- Those grounds starred on the aide-mémoire above have a 2 months provision (& ground 9), and those double starred have a 2 weeks provision & grounds 7B, 12, 13, 14ZA, 14A, 15 & 17).

- A tenant’s notice to quit is extended to 2 months unless a shorter period is agreed – in or outside the tenancy agreement – between the parties – clause 14.

Shared Ownership

Finally, it is worth addressing the proposed fundamental change to the tenancy status of shared ownership. The current position is:

(a) Most landlords in this field are PRPs rather than local housing authorities.

(b) Shared ownership tenants may have a long tenancy term akin to a long lease but they are subject to the “ordinary” tenancy provisions of the Housing Act 1988: Richardson v Midland Heart Ltd [2008] L.&T.R. 31.

(c) Forfeiture proceedings are therefore only required if the assured shorthold tenancy status is lost – e.g. the tenant or all of the joint tenants are no longer living at the demised premises as their only or principal home.

(d) In such a case they are ‘long leases’ for First-tier Tribunal purposes and so section 168 of the Commonhold & Leasehold Reform Act 2002 applies (i.e. determination of breach before s.146 notice): s.169(5), CLRA.

Clause 21 of the Bill makes provision, by way of amendment to Schedule 1 of the 1988 Act, for tenancies of more than seven years from their grant, such as a shared ownership agreement, being outside the assured tenancy regime. My PowerPoint slide at the webinar referred to above simply said:

- New paragraph to Schedule 1, Housing Act 1988 (tenancies which cannot be assured tenancies)

- This will encompass fixed term tenancies of more than 7 years from date of grant of tenancy

- In those cases where either possession proceedings are commenced – or if not commenced the notice seeking possession has been served and is still ‘live’ (i.e. 12 months has not expired since it’s service – s. 8(3), Housing Act 1988) – before this provision is brought into force, the SO arrangement remains assured

- Possession proceedings will therefore be exclusively a question of forfeiture

- Landlords will have to be very alive to waiver actions (e.g. acceptance or demand of rent)/impact/Right to manage/enfranchisement/lease extension? Avon Ground Rents Ltd v Canary Gateway (Block A) RTM Co Ltd

Shared ownership is fraught with difficulties as it is, and it is critical for PRPs which operate such schemes to ensure that they understand how to seek recovery of possession through the forfeiture route and avoid pitfalls, most obviously that of waiver.

[1] Clauses 1 and 2 – a new section of the Housing Act 1988, section 4A, will provide that purported fixed-term tenancies will be treated as periodic referable to the rent periods (not exceeding monthly). To abolish assured shorthold tenancies, clause 2 simply omits Chapter 2 of Part 1 (sections 19A-23) of the 1988 Act.

[2] See their 21 September 2018 press release.

[3] See section 6A and 20B of the 1988 Act – both will be removed according to clause 2 of the Bill.